7.2 2. Primary Categories of SDM Techniques

Species Distribution Modeling (SDM) techniques are diverse, each tailored to specific types of data and research objectives. They can be broadly categorized into four main groups:

7.2.1 2.1. Envelopes and Distance-Based Methods

Overview: These methods define the environmental conditions (or “envelopes”) suitable for a species or use similarity metrics to assess habitat suitability.

7.2.1.1 BIOCLIM

-

What it does:

Identifies climatic envelopes by considering species occurrences within the range of environmental conditions. -

Strengths:

- Simple and intuitive.

- Effective for presence-only data.

-

Limitations:

- Assumes all conditions within the envelope are equally suitable.

- Use Case: Mapping climatic suitability for plant species based on temperature and precipitation.

7.2.1.2 DOMAIN

-

What it does:

Calculates environmental similarity using Gower’s distance to assess habitat suitability. -

Strengths:

- Easy to implement.

- Handles multi-dimensional environmental data well.

-

Limitations:

- Sensitive to outliers.

- Use Case: Predicting the distribution of insect species based on microhabitat conditions.

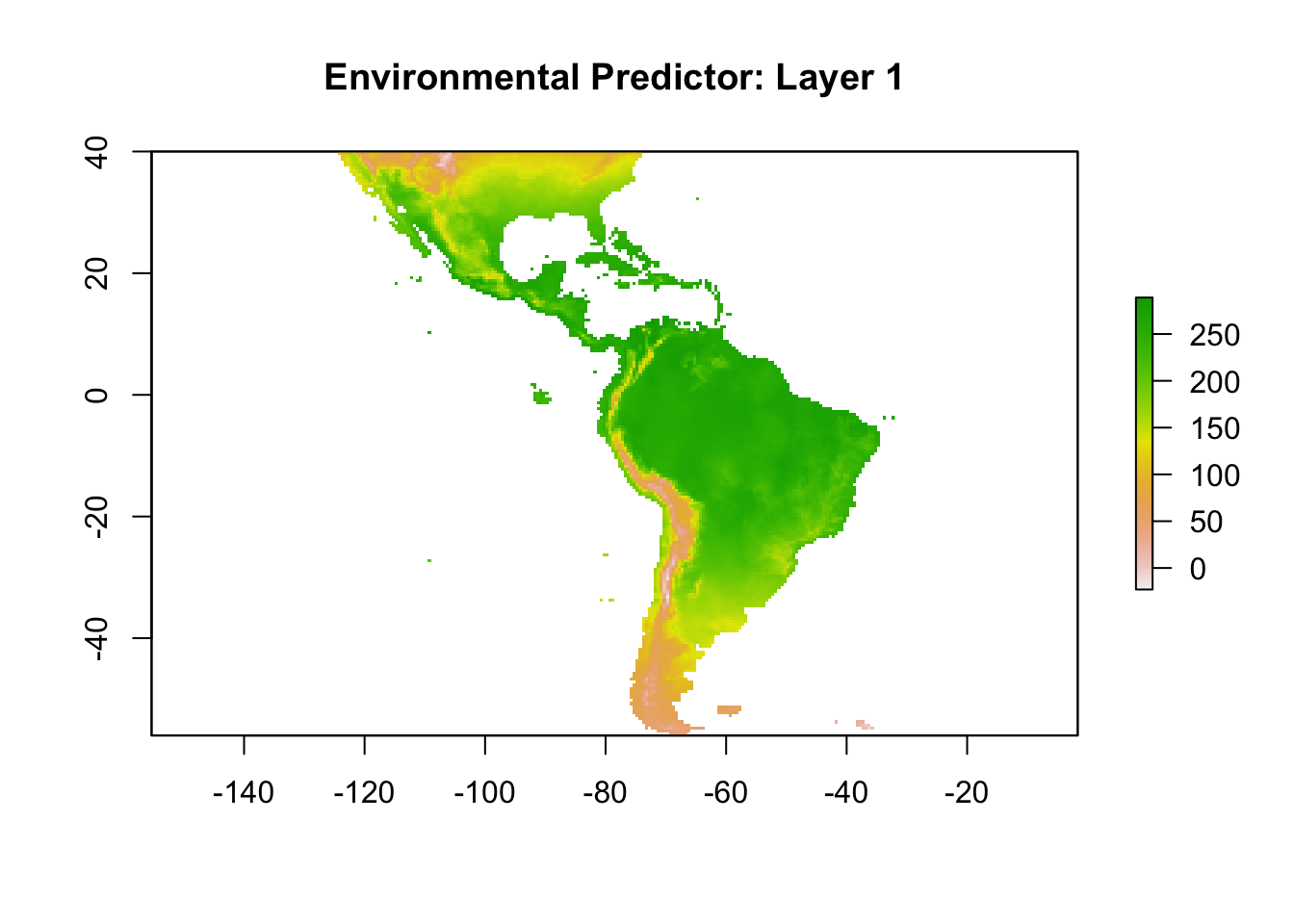

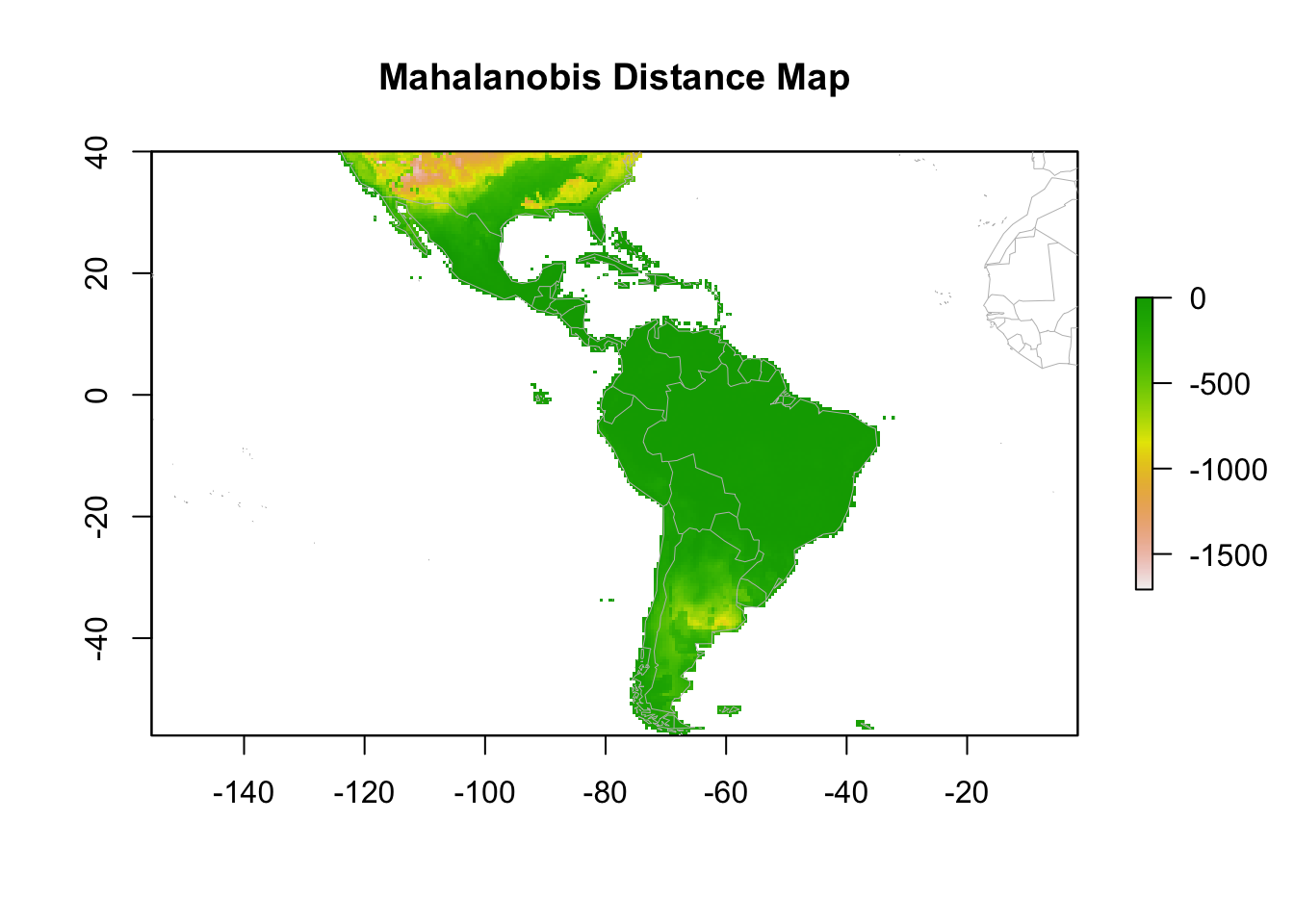

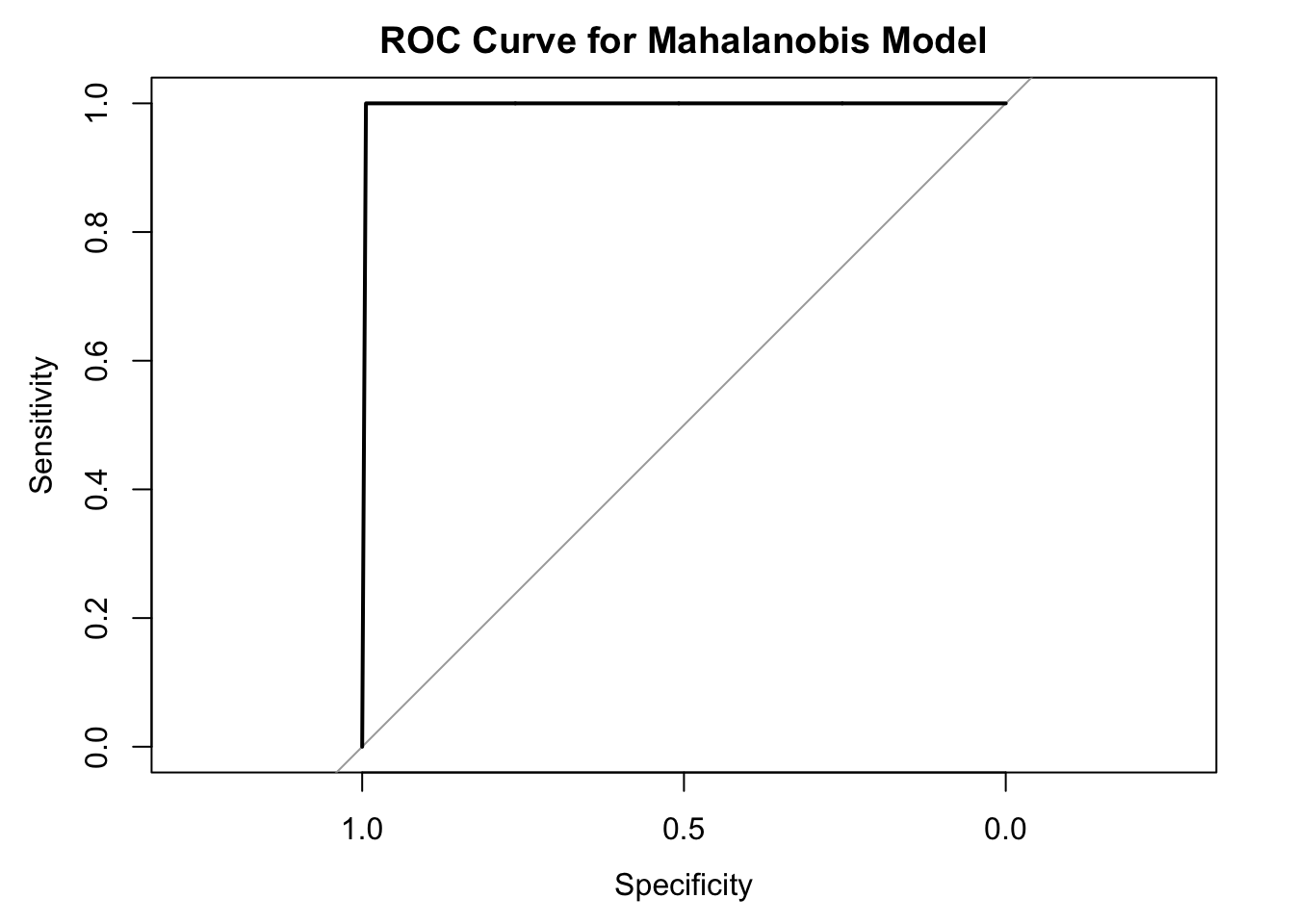

7.2.1.3 Mahalanobis Distance

-

What it does:

Measures multivariate similarity based on the covariance structure of the data. -

Strengths:

- Robust to multicollinearity among predictors.

- Suitable for continuous environmental data.

-

Limitations:

- Assumes a linear relationship between variables.

- Use Case: Modeling habitat suitability for mammals in forested landscapes.

7.2.1.4 Ecological Niche Factor Analysis (ENFA)

-

What it does:

Identifies the species’ ecological niche by comparing environmental conditions at presence locations to the overall study area. -

Strengths:

- Provides insights into ecological specialization.

- Useful for rare species with limited data.

-

Limitations:

- Requires careful interpretation of niche parameters.

- Use Case: Studying niche shifts in invasive species.

7.2.2 2.2. Regression-Based Methods

Overview: These methods analyze the relationship between species occurrences and environmental predictors, often providing interpretable models.

7.2.2.1 Generalized Linear Models (GLMs)

-

What it does:

Models species-environment relationships using linear predictors and a link function. -

Strengths:

- Flexible and interpretable.

- Handles presence-absence data well.

-

Limitations:

- Assumes linear or predefined relationships.

- Use Case: Analyzing the effect of temperature and precipitation on bird distributions.

7.2.2.2 Generalized Additive Models (GAMs)

-

What it does:

Extends GLMs by allowing non-linear relationships through smooth functions. -

Strengths:

- Captures complex, non-linear relationships.

- Highly flexible.

-

Limitations:

- Computationally intensive for large datasets.

- Use Case: Modeling species distribution along temperature gradients.

7.2.2.3 Multivariate Adaptive Regression Splines (MARS)

-

What it does:

Breaks predictor relationships into piecewise linear segments. -

Strengths:

- Handles complex, non-linear interactions.

- Automatic feature selection.

-

Limitations:

- Requires careful parameter tuning.

- Use Case: Predicting fish distributions in aquatic systems.

7.2.3 2.3. Decision Tree Methods

Overview: Decision trees split data into hierarchical branches, providing interpretable models for species-environment relationships.

7.2.3.1 Classification and Regression Trees (CART)

-

What it does:

Builds a decision tree to classify species presence or absence based on environmental thresholds. -

Strengths:

- Simple and intuitive.

- Handles non-linear relationships well.

-

Limitations:

- Prone to overfitting without pruning.

- Use Case: Identifying habitat thresholds for amphibian species based on wetland characteristics.

7.2.4 2.4. Machine Learning Approaches

Overview: Advanced techniques that excel in handling complex data with high dimensionality and interactions.

7.2.4.1 Maximum Entropy (MaxEnt)

-

What it does:

Predicts species distribution by maximizing entropy under environmental constraints. -

Strengths:

- Works well with presence-only data.

- Easy to interpret.

-

Limitations:

- May overfit with small datasets.

- Use Case: Mapping potential distributions of endangered plants.

7.2.4.2 Random Forests

-

What it does:

Combines multiple decision trees to improve predictive accuracy. -

Strengths:

- Handles large datasets and complex interactions.

- Robust to overfitting.

-

Limitations:

- Difficult to interpret compared to simpler models.

- Use Case: Predicting bird distributions across diverse habitats.

7.2.4.3 Boosted Regression Trees (BRT/GBM)

-

What it does:

Sequentially builds decision trees to minimize prediction errors. -

Strengths:

- High predictive accuracy.

- Handles non-linear relationships and interactions.

-

Limitations:

- Computationally expensive.

- Use Case: Modeling shifts in species ranges under future climate scenarios.

7.2.4.4 Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs)

-

What it does:

Mimics human brain processes to model complex relationships. -

Strengths:

- Highly flexible and powerful for large datasets.

- Captures non-linear relationships.

-

Limitations:

- Requires large training datasets.

- Difficult to interpret.

- Use Case: Predicting aquatic species distributions based on multiple predictors.

7.2.4.5 Support Vector Machines (SVMs)

-

What it does:

Separates species presence and absence data using hyperplanes in high-dimensional space. -

Strengths:

- Effective for small datasets with complex boundaries.

- Handles high-dimensional data well.

-

Limitations:

- Computationally intensive.

- Use Case: Mapping species distributions in fragmented landscapes.

7.2.5 Key Takeaways

- Different SDM techniques cater to different types of data (e.g., presence-only, presence-absence) and study goals.

- Envelopes and Distance-Based Methods are simple and intuitive but limited in complexity.

- Regression-Based Methods balance interpretability and flexibility.

- Decision Tree Methods are easy to understand but can overfit.

- Machine Learning Approaches provide powerful tools for complex, high-dimensional data but require careful tuning and interpretation.