4 Spartial Data in R

4.0.1 1. Introduction

In the previous section, we learned about spatial data and why it’s important for understanding species distribution and the environment. Now, we will move forward by learning how to actually work with this data in R.

This part of the tutorial will show you step by step:

- How to create vector data (like points, lines, and polygons).

- How to make raster layers and combine them into stacks and bricks.

- How to set and change projections so that your data lines up correctly on a map.

- How to get real-world data, like climate information and species locations, which you can use to build models.

By following along, you’ll learn basic methods for handling both vector and raster data in R. You’ll also get familiar with common GIS tasks like reading, writing, and transforming spatial data.

Let’s start! 🌍

4.1 ### 2. Working with Vector Data in R

Vector data includes points, lines, and polygons. In this section, we will focus on creating point data, converting it into a spatial object, and adding attribute data.

4.1.0.1 2.1. Creating Point Data

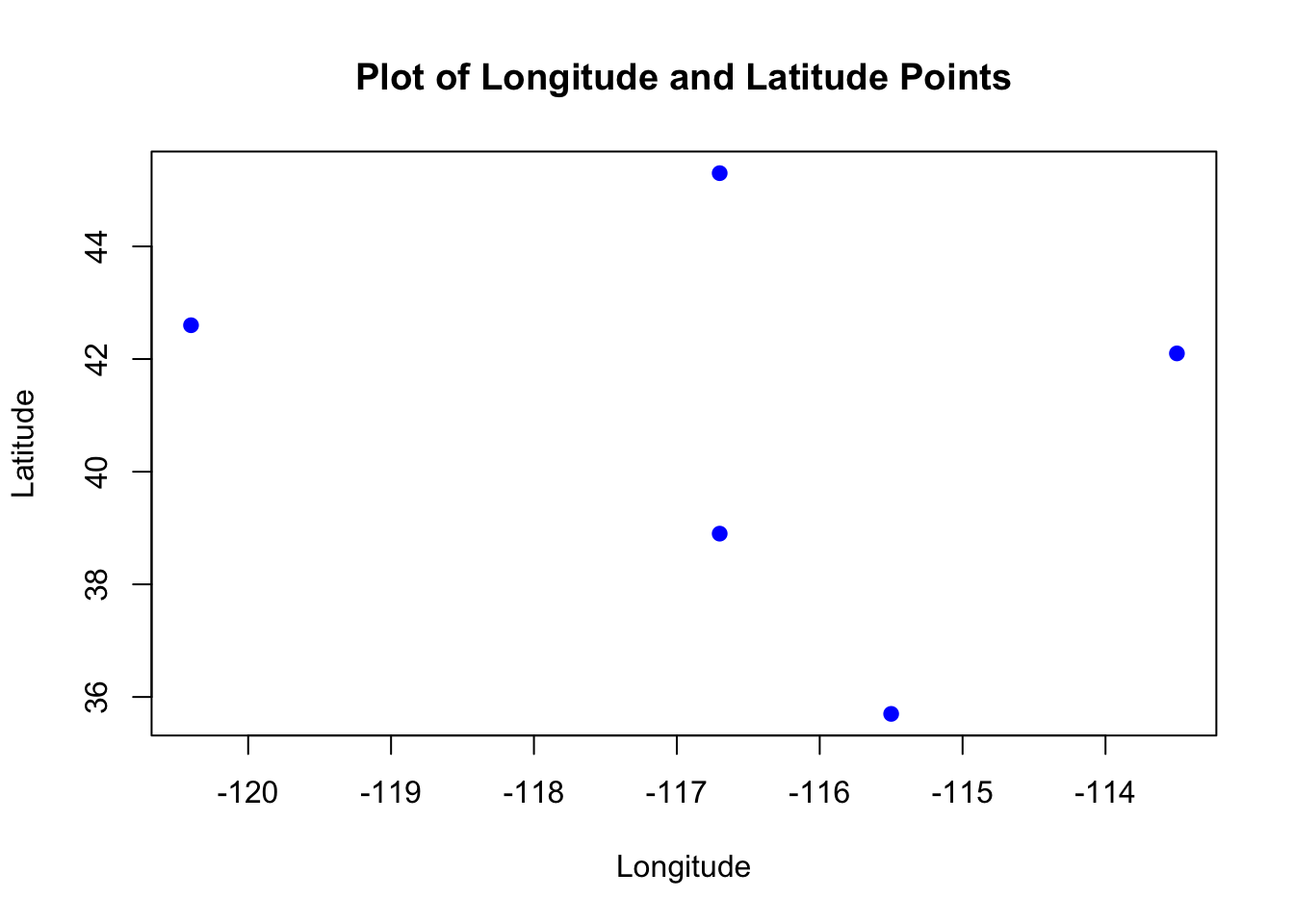

To start, we need to create a set of points using longitude and latitude values. In R, this can be done using simple vectors.

# Creating vectors for longitude and latitude

longitude <- c(-116.7, -120.4, -116.7, -113.5, -115.5)

latitude <- c(45.3, 42.6, 38.9, 42.1, 35.7)

# Combine into a matrix of coordinates

lonlat <- cbind(longitude, latitude)

# Plot the points

plot(lonlat, pch = 19, col = "blue", xlab = "Longitude", ylab = "Latitude",

main = "Plot of Longitude and Latitude Points")

-

Order matters: Always specify coordinates as

(longitude, latitude), not(latitude, longitude). This follows the common geographic convention. - The

plot()function gives a quick view of the points.

4.1.0.2 2.2. Converting to a Spatial Object

Although we have plotted the points, they are not yet considered spatial data. To work with spatial data, we need to convert these points into a SpatialPoints object.

# Load the 'sp' package for spatial data handling

library(sp)

# Create a SpatialPoints object

pts <- SpatialPoints(lonlat)

# Check the class of the object

class(pts)

#> [1] "SpatialPoints"

#> attr(,"package")

#> [1] "sp"The sp package is a core tool for handling vector data in R. SpatialPoints objects store spatial information, but they don’t yet have any associated attributes.

4.1.0.3 Assigning a Coordinate Reference System (CRS)

A CRS defines how the spatial data relates to locations on Earth. Without a CRS, your points won’t align properly with other spatial datasets.

# Assign a CRS to the SpatialPoints object

crs_string <- "+proj=longlat +datum=WGS84"

pts <- SpatialPoints(lonlat, proj4string = CRS(crs_string))

pts

#> SpatialPoints:

#> longitude latitude

#> [1,] -116.7 45.3

#> [2,] -120.4 42.6

#> [3,] -116.7 38.9

#> [4,] -113.5 42.1

#> [5,] -115.5 35.7

#> Coordinate Reference System (CRS) arguments:

#> +proj=longlat +datum=WGS84 +no_defsAlways assign a CRS when working with spatial data!

In most cases, use "+proj=longlat +datum=WGS84" for data with longitude and latitude coordinates.

4.1.0.4 2.3. Creating a SpatialPointsDataFrame

A SpatialPointsDataFrame combines spatial data with attribute data. Let’s add some random precipitation values to our points.

# Create a data frame of attribute data

set.seed(42) # For reproducibility

precipValue <- runif(nrow(lonlat), min = 0, max = 100) # Random precipitation values

df <- data.frame(ID = 1:nrow(lonlat), precip = precipValue)

# Combine the SpatialPoints object with the attribute data

ptsdf <- SpatialPointsDataFrame(pts, data = df)

# View the first few rows of the data

head(ptsdf@data)

#> ID precip

#> 1 1 91.48060

#> 2 2 93.70754

#> 3 3 28.61395

#> 4 4 83.04476

#> 5 5 64.174554.1.0.5 Output Check

You can access both the coordinates and attributes separately.

# Access the spatial coordinates

ptsdf@coords

#> longitude latitude

#> [1,] -116.7 45.3

#> [2,] -120.4 42.6

#> [3,] -116.7 38.9

#> [4,] -113.5 42.1

#> [5,] -115.5 35.7

# Access the attribute data

ptsdf@data

#> ID precip

#> 1 1 91.48060

#> 2 2 93.70754

#> 3 3 28.61395

#> 4 4 83.04476

#> 5 5 64.17455- Use

ptsdf@coordsto extract the spatial coordinates. - Use

ptsdf@datato extract the non-spatial attribute data.

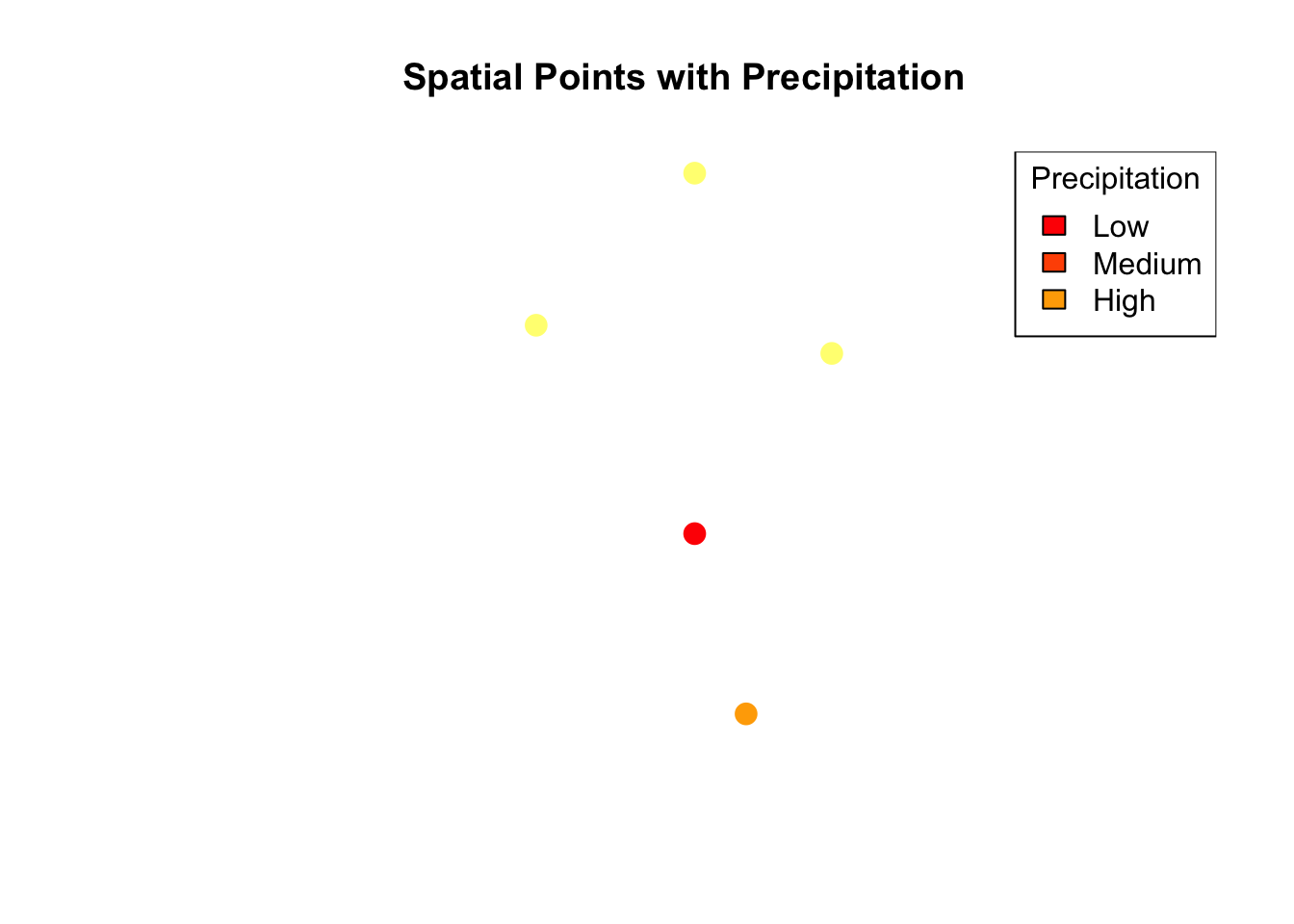

4.1.0.6 Plotting the Data

We can now visualize the points on a simple plot, coloring them based on precipitation values.

# Plot with color based on precipitation

plot(ptsdf, pch = 19, col = heat.colors(5)[cut(ptsdf$precip, breaks = 5)],

main = "Spatial Points with Precipitation", cex = 1.5)

legend("topright", legend = c("Low", "Medium", "High"), fill = heat.colors(5),

title = "Precipitation")

4.1.1 Summary

- We learned how to create point data using longitude and latitude.

- We converted the points into a spatial object using the

sppackage. - We added attribute data to create a

SpatialPointsDataFrame. - Finally, we plotted the points with precipitation values.

4.1.2 3. Creating and Manipulating Raster Data in R

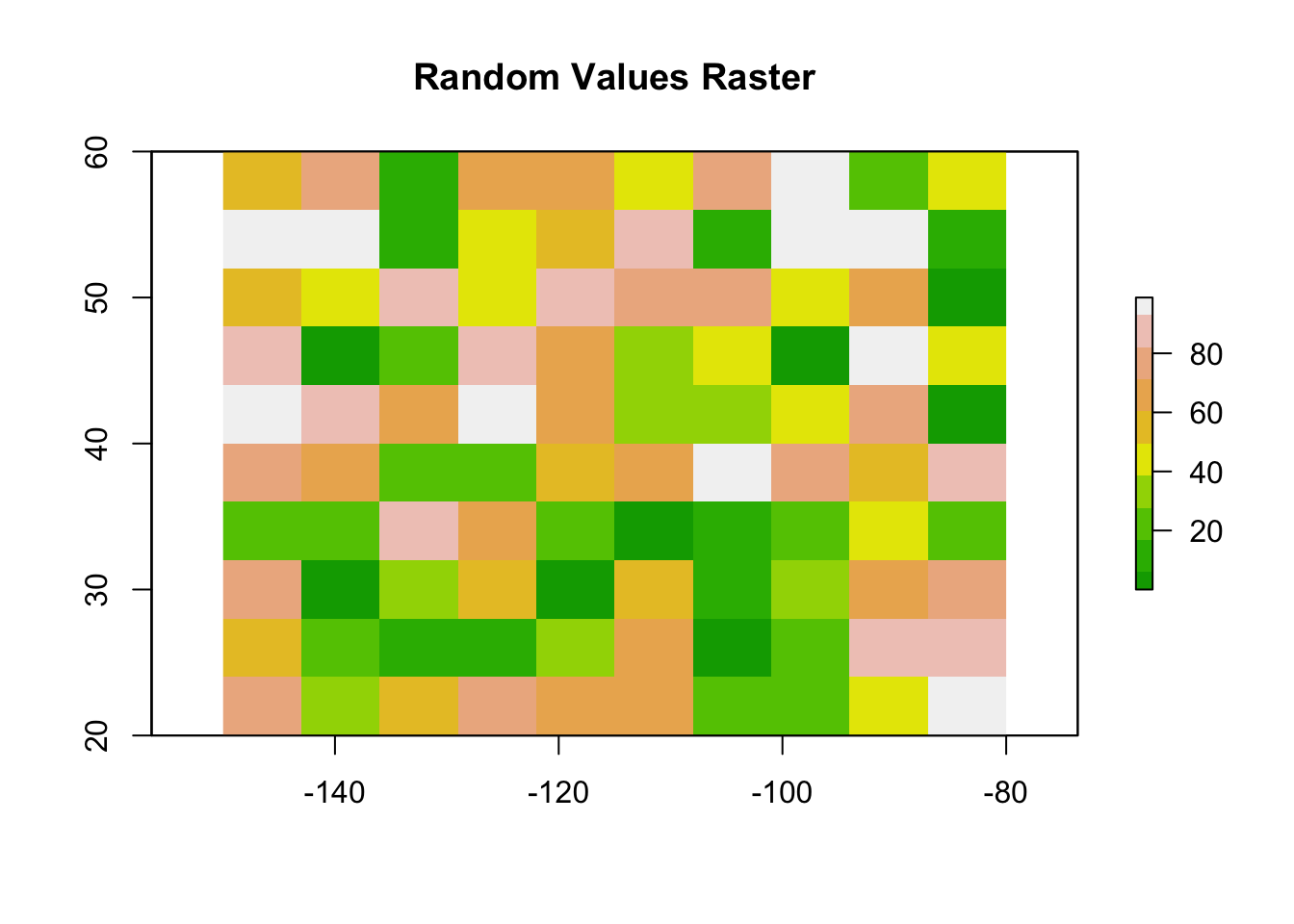

4.1.2.1 3.1. Creating a RasterLayer

A raster represents spatial data as a grid of cells, where each cell has a value. This is useful for continuous data like temperature, elevation, or land cover.

We’ll start by creating a blank raster with 10 columns and 10 rows, and we’ll define its extent (the geographic area it covers).

# Load the 'raster' package

library(raster)

# Create a blank raster with specific extent and resolution

r <- raster(ncol = 10, nrow = 10, xmx = -80, xmn = -150, ymn = 20, ymx = 60)

# Print raster details

r

#> class : RasterLayer

#> dimensions : 10, 10, 100 (nrow, ncol, ncell)

#> resolution : 7, 4 (x, y)

#> extent : -150, -80, 20, 60 (xmin, xmax, ymin, ymax)

#> crs : +proj=longlat +datum=WGS84 +no_defs- The raster has 10 columns and 10 rows, meaning there are 100 cells in total.

- The extent specifies the geographic boundaries:

-

xmn = -150andxmx = -80(longitude range) -

ymn = 20andymx = 60(latitude range)

-

- The default Coordinate Reference System (CRS) is

WGS84, which uses longitude and latitude.

4.1.2.2 3.2. Adding Values to the Raster

Now that we have a blank raster, we can assign values to its cells. Let’s assign random values between 0 and 100 using the runif() function, which generates random numbers.

# Assign random values to the raster cells

values(r) <- runif(ncell(r), min = 0, max = 100)

# Plot the raster

plot(r, main = "Random Values Raster", col = terrain.colors(10))

- The

ncell()function returns the total number of cells in the raster. - The

terrain.colors()function is used to create a nice color gradient for the plot.

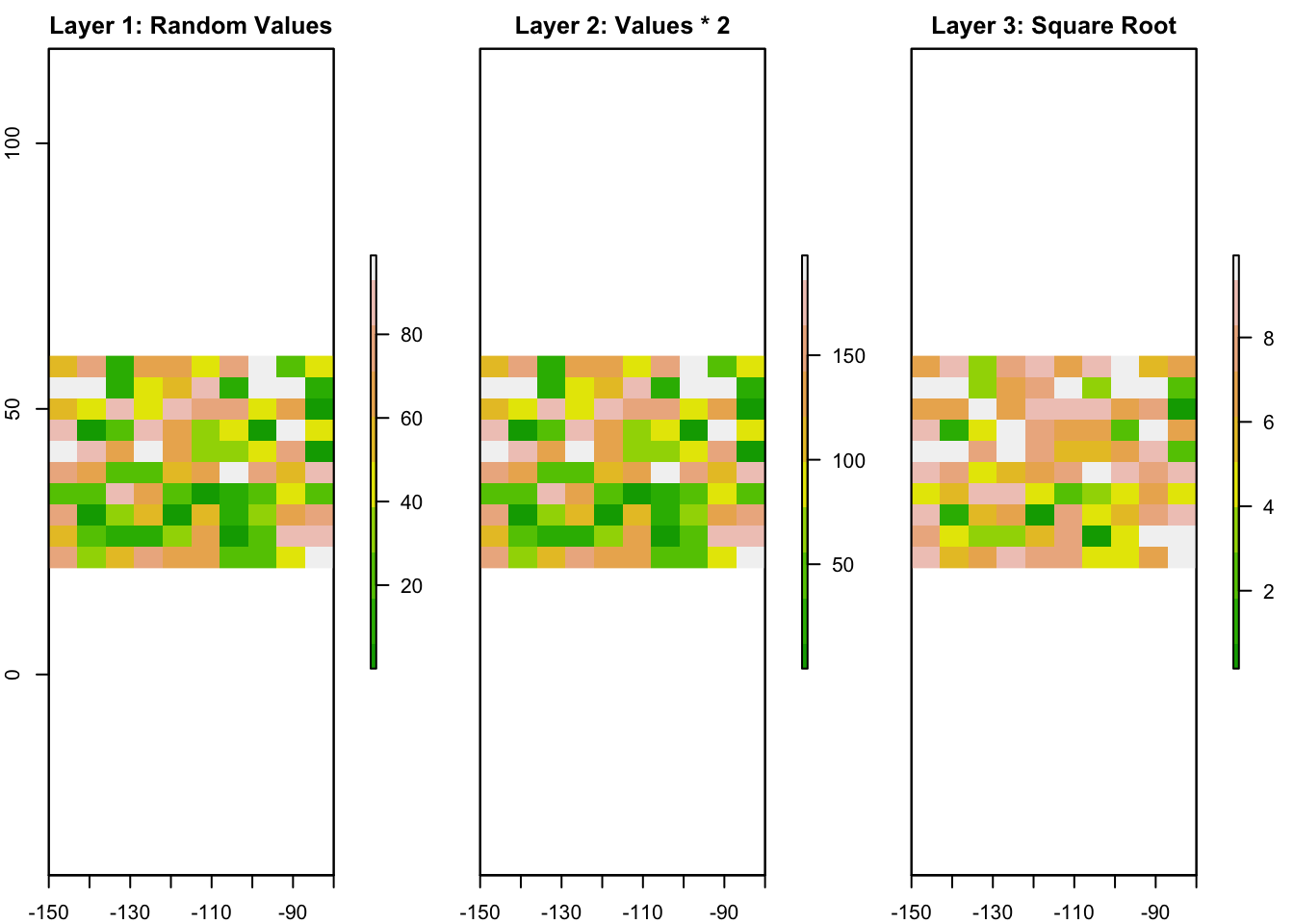

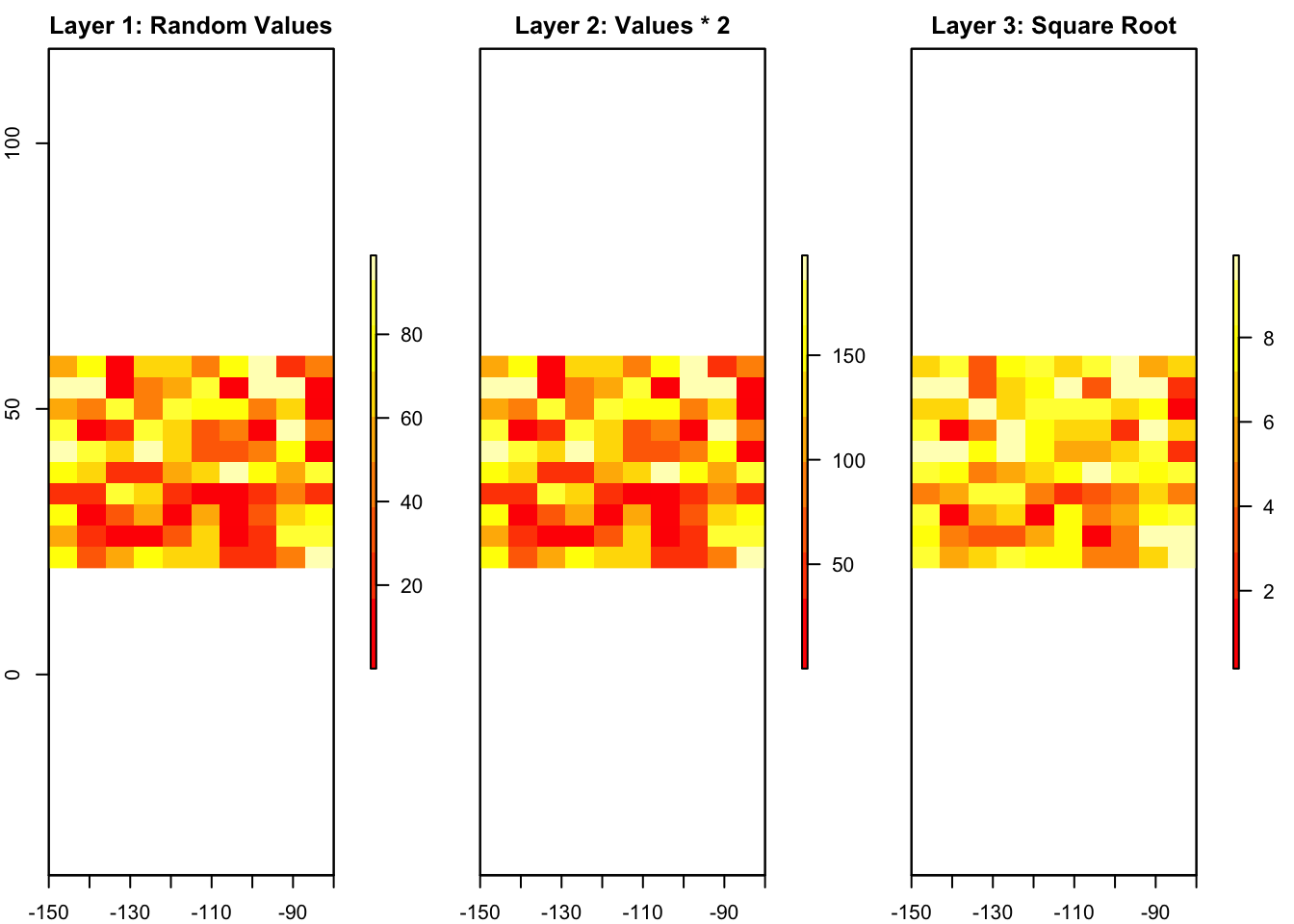

4.1.2.3 3.3. Creating a RasterStack

A RasterStack is a collection of multiple rasters with the same extent and resolution. This is useful when you have multiple layers of data for the same area, such as temperature, precipitation, and elevation.

Let’s create two more rasters and stack them together.

# Create two more rasters by performing operations on the original raster

r2 <- r * 2 # Multiply all values by 2

r3 <- sqrt(r) # Take the square root of all values

# Create a RasterStack

s <- stack(r, r2, r3)

# Plot the RasterStack with enhanced visualization

plot(s, main = c("Layer 1: Random Values", "Layer 2: Values * 2", "Layer 3: Square Root"),

col = terrain.colors(10), nr = 1)

- All rasters in the stack must have the same resolution and extent.

- You can stack as many rasters as you need.

4.1.2.4 3.4. Creating a RasterBrick

A RasterBrick is similar to a RasterStack, but it is stored more efficiently in memory. This makes it faster to process when working with large datasets.

# Create a RasterBrick from the RasterStack

b <- brick(s)

# Plot the RasterBrick with enhanced visualization

plot(b, main = c("Layer 1: Random Values", "Layer 2: Values * 2", "Layer 3: Square Root"),

col = heat.colors(10), nr = 1)

- Use a

RasterBrickwhen you need better performance and memory efficiency. - A

RasterBrickis particularly useful when dealing with large datasets, such as satellite imagery or time-series data.

4.2 ### 4. Working with Coordinate Reference Systems (CRS)

4.2.0.1 4.1. Assigning and Transforming CRS

When working with spatial data, ensuring that all layers share a common CRS is crucial for proper alignment and accurate analysis. Let’s walk through assigning a CRS and transforming it to a new one using vector and raster data.

4.2.0.1.1 Assigning a CRS to Vector Data

# Load necessary library

library(sf)

#> Linking to GEOS 3.11.0, GDAL 3.5.3, PROJ 9.1.0; sf_use_s2()

#> is TRUE

# Create sample point data

longitude <- c(-116.7, -120.4, -116.7, -113.5, -115.5)

latitude <- c(45.3, 42.6, 38.9, 42.1, 35.7)

pts <- data.frame(longitude, latitude)

# Convert to an sf object and assign WGS84 CRS

sf_pts <- st_as_sf(pts, coords = c("longitude", "latitude"), crs = 4326)

# View CRS of the spatial object

st_crs(sf_pts)

#> Coordinate Reference System:

#> User input: EPSG:4326

#> wkt:

#> GEOGCRS["WGS 84",

#> ENSEMBLE["World Geodetic System 1984 ensemble",

#> MEMBER["World Geodetic System 1984 (Transit)"],

#> MEMBER["World Geodetic System 1984 (G730)"],

#> MEMBER["World Geodetic System 1984 (G873)"],

#> MEMBER["World Geodetic System 1984 (G1150)"],

#> MEMBER["World Geodetic System 1984 (G1674)"],

#> MEMBER["World Geodetic System 1984 (G1762)"],

#> MEMBER["World Geodetic System 1984 (G2139)"],

#> ELLIPSOID["WGS 84",6378137,298.257223563,

#> LENGTHUNIT["metre",1]],

#> ENSEMBLEACCURACY[2.0]],

#> PRIMEM["Greenwich",0,

#> ANGLEUNIT["degree",0.0174532925199433]],

#> CS[ellipsoidal,2],

#> AXIS["geodetic latitude (Lat)",north,

#> ORDER[1],

#> ANGLEUNIT["degree",0.0174532925199433]],

#> AXIS["geodetic longitude (Lon)",east,

#> ORDER[2],

#> ANGLEUNIT["degree",0.0174532925199433]],

#> USAGE[

#> SCOPE["Horizontal component of 3D system."],

#> AREA["World."],

#> BBOX[-90,-180,90,180]],

#> ID["EPSG",4326]]- The EPSG code

4326corresponds to the WGS84 geographic CRS, commonly used for data with longitude and latitude coordinates. - Using

st_as_sf()converts the data frame into a spatial object.

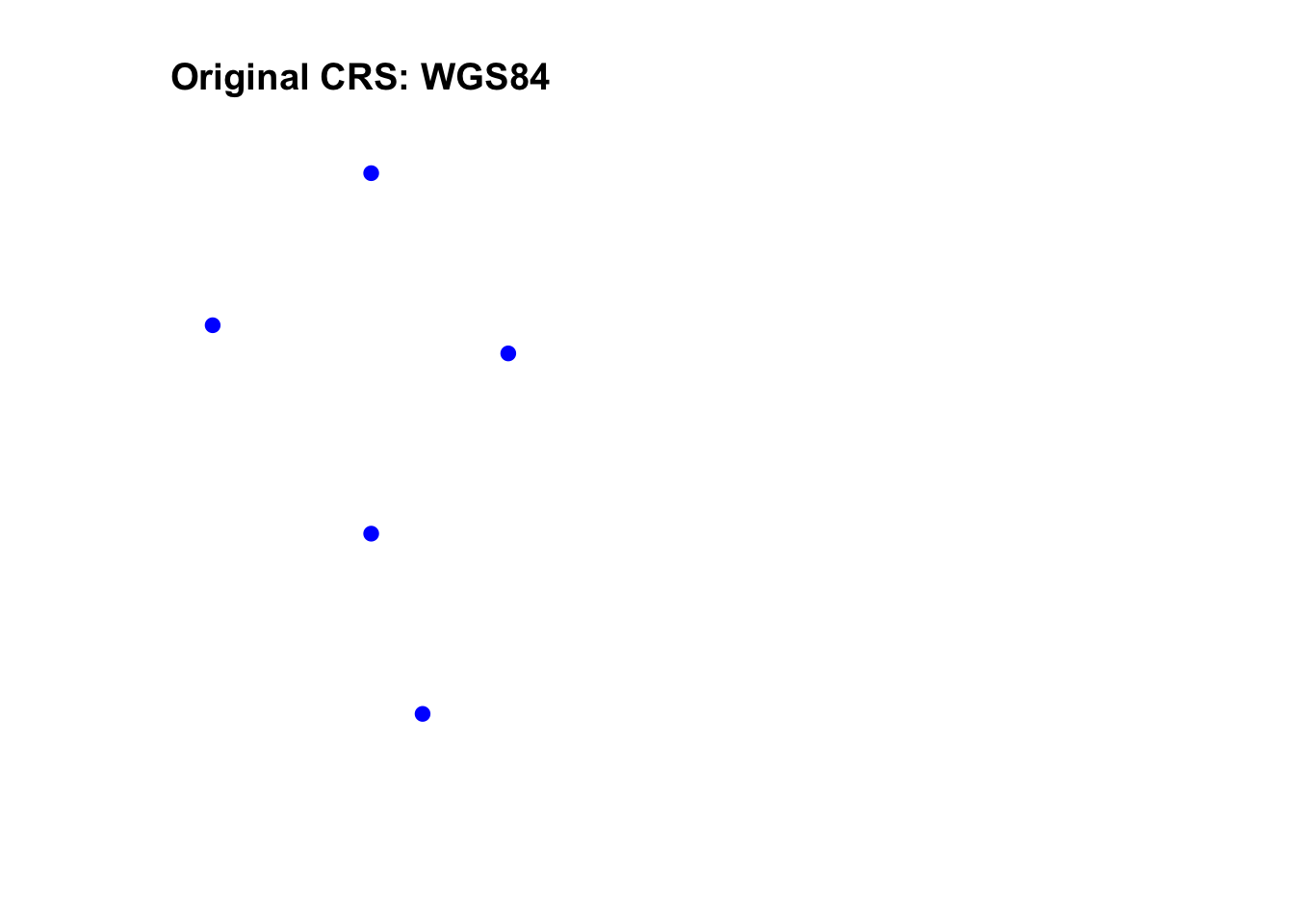

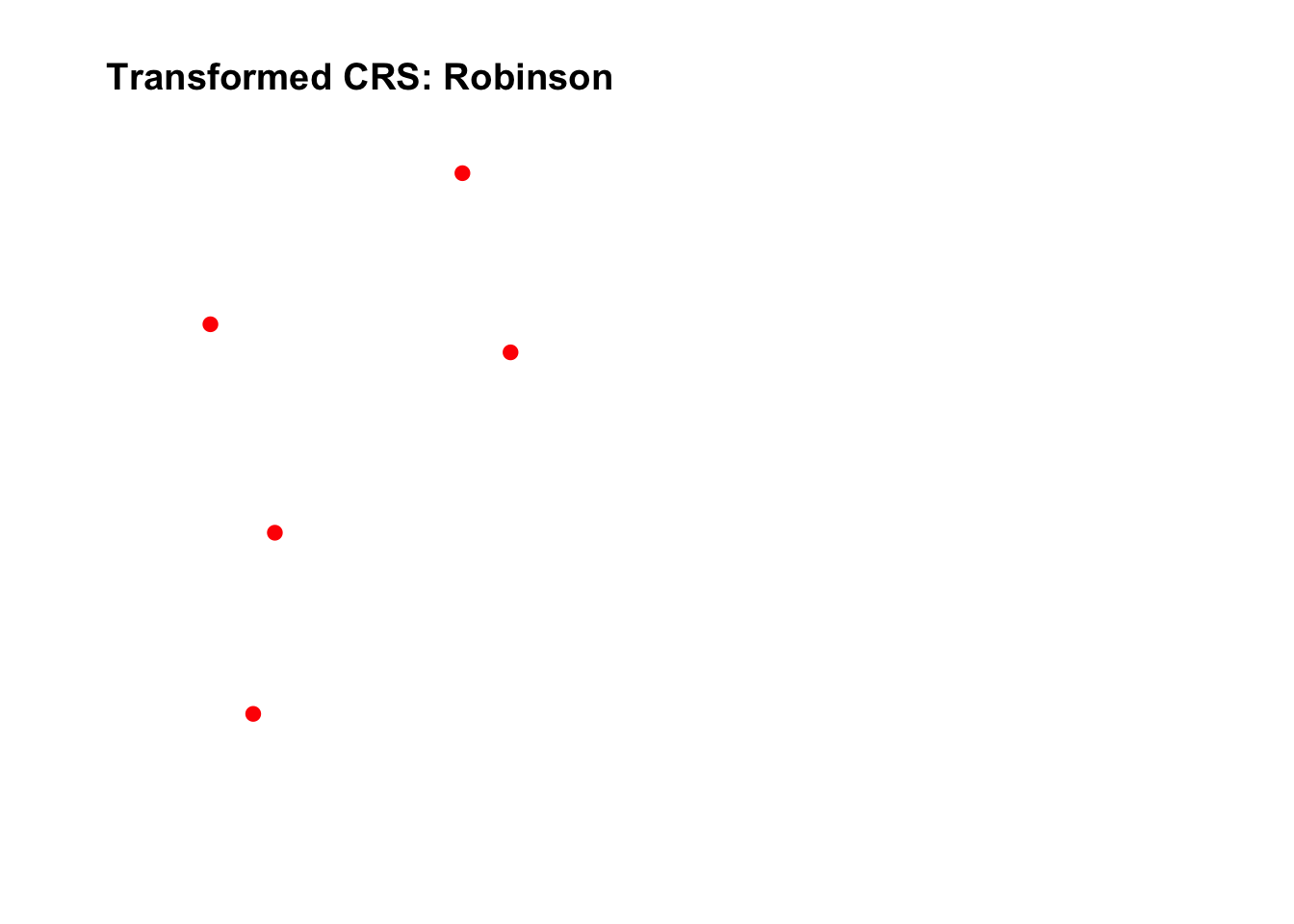

4.2.0.1.2 Transforming Vector Data to a New CRS

Let’s transform the spatial data from WGS84 to a Robinson projection.

# Define the new CRS (Robinson projection)

new_crs <- "+proj=robin +datum=WGS84"

# Transform the spatial points to the new CRS

sf_pts_transformed <- st_transform(sf_pts, crs = new_crs)

# Plot the original and transformed data side by side

par(mfrow = c(1, 2)) # Set plotting layout

# Original data in WGS84

plot(sf_pts, main = "Original CRS: WGS84", col = "blue", pch = 19)

# Transformed data in Robinson projection

plot(sf_pts_transformed, main = "Transformed CRS: Robinson", col = "red", pch = 19)

- Different CRSs can distort distances, areas, and angles differently, depending on their projection method.

- Always choose a CRS that fits your analysis needs (e.g., UTM for local-scale accuracy, Albers Equal-Area for area-preserving studies).

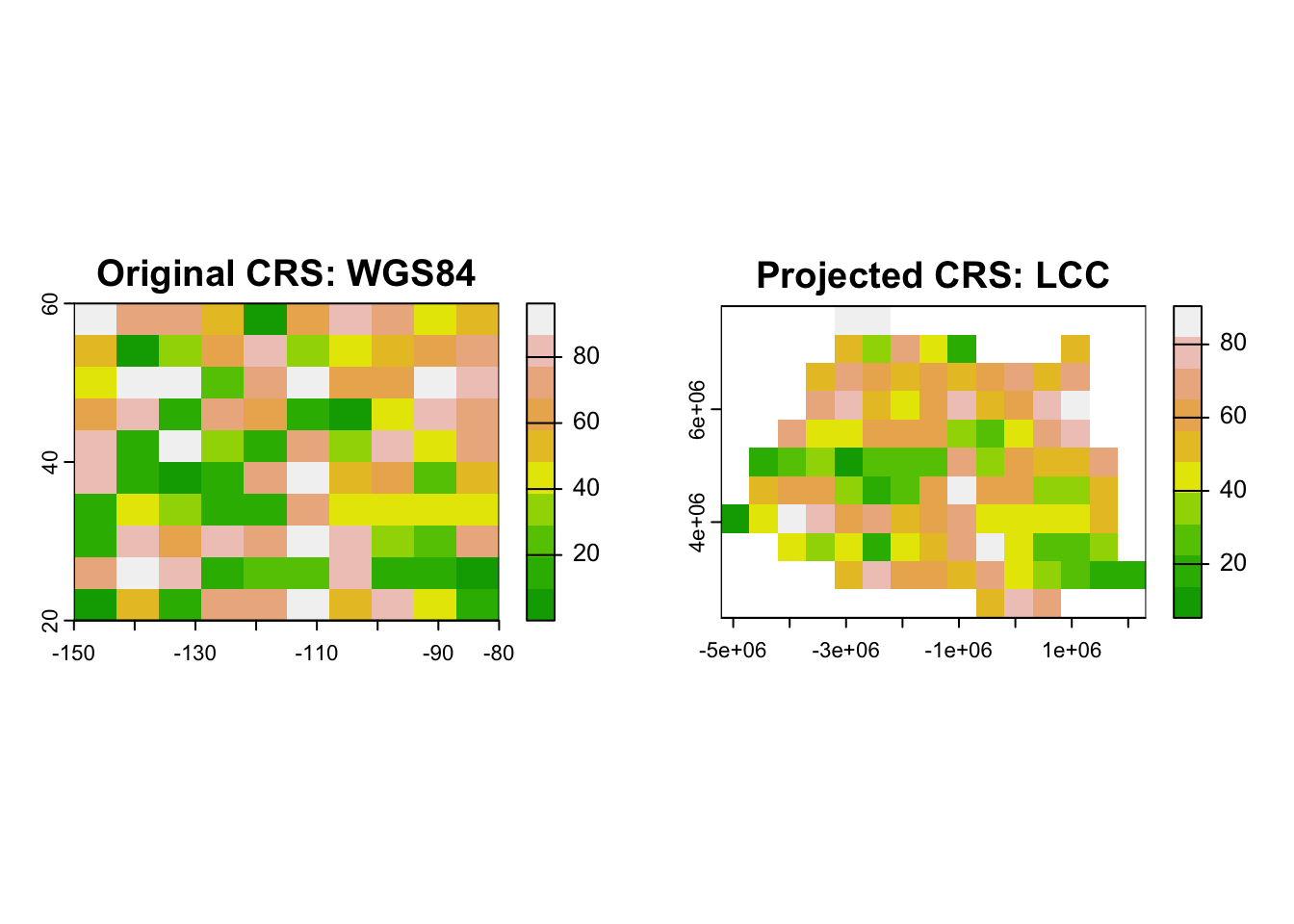

4.2.0.2 4.2. Projecting Raster Data

Projecting raster data involves recalculating cell values and adjusting the resolution to fit the new CRS. Let’s demonstrate this using a raster dataset.

4.2.0.2.1 Reprojecting a Raster

# Load necessary library

library(terra)

#> terra 1.8.5

# Create a sample raster

r <- rast(ncol = 10, nrow = 10, xmin = -150, xmax = -80, ymin = 20, ymax = 60, crs = "EPSG:4326")

values(r) <- runif(ncell(r), min = 0, max = 100) # Assign random values

# Define a new CRS (Lambert Conformal Conic projection)

new_crs_raster <- "+proj=lcc +lat_1=48 +lat_2=33 +lon_0=-100 +datum=WGS84"

# Project the raster to the new CRS

r_projected <- project(r, new_crs_raster)

# Plot original and reprojected raster

par(mfrow = c(1, 2))

# Original raster in WGS84

plot(r, main = "Original CRS: WGS84", col = terrain.colors(10))

# Projected raster in Lambert Conformal Conic

plot(r_projected, main = "Projected CRS: LCC", col = terrain.colors(10))

- The

project()function from the terra package is used for raster reprojection. - Ensure that the target CRS is defined using PROJ.4 strings or EPSG codes.

4.2.1 Key Takeaways

- Always ensure that your spatial datasets use the same CRS before performing analysis.

- Use

st_crs()andst_transform()for vector data andcrs()andproject()for raster data. - Choose appropriate CRSs based on the scope and goals of your project.

4.3 ### 5. Reading and Writing Spatial Data

4.3.0.1 5.1. Reading Shapefiles and Rasters

Working with spatial data often starts by reading external files such as shapefiles and raster datasets. R provides convenient functions to load these files into spatial objects for analysis.

4.3.0.1.1 Reading a Shapefile

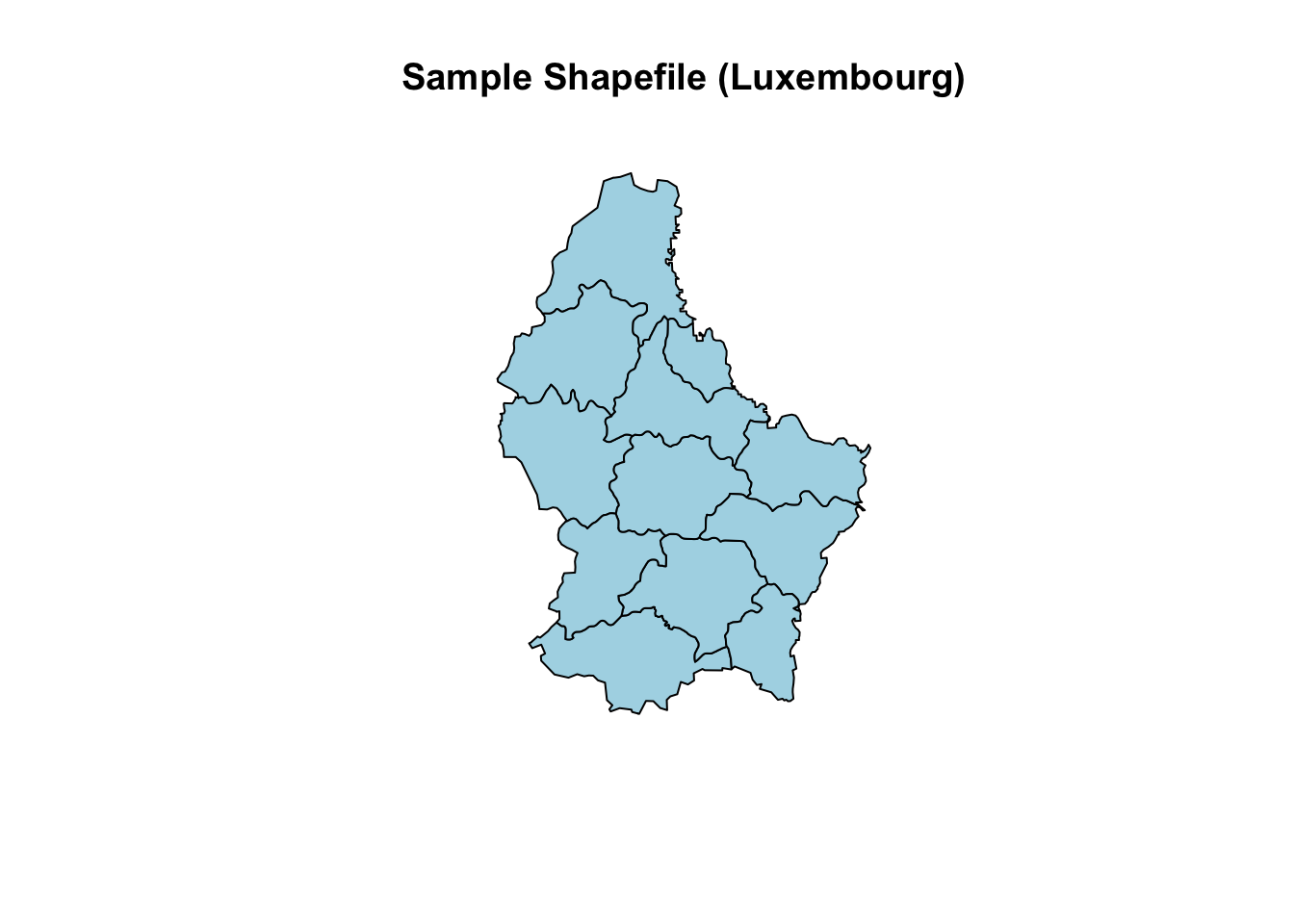

Let’s read a sample shapefile provided by the raster package.

# Load necessary library

library(raster)

# Read a sample shapefile (comes with the 'raster' package)

shapefile_path <- system.file("external/lux.shp", package = "raster")

shape_data <- shapefile(shapefile_path)

# Print basic information about the shapefile

print(shape_data)

#> class : SpatialPolygonsDataFrame

#> features : 12

#> extent : 5.74414, 6.528252, 49.44781, 50.18162 (xmin, xmax, ymin, ymax)

#> crs : +proj=longlat +datum=WGS84 +no_defs

#> variables : 5

#> names : ID_1, NAME_1, ID_2, NAME_2, AREA

#> min values : 1, Diekirch, 1, Capellen, 76

#> max values : 3, Luxembourg, 12, Wiltz, 312

# Plot the shapefile

plot(shape_data, main = "Sample Shapefile (Luxembourg)", col = "lightblue")

- The function

shapefile()reads vector data in shapefile format and loads it as aSpatial*object. - The

system.file()function retrieves the path to a sample shapefile provided by the package.

4.3.0.1.2 Reading a Raster File

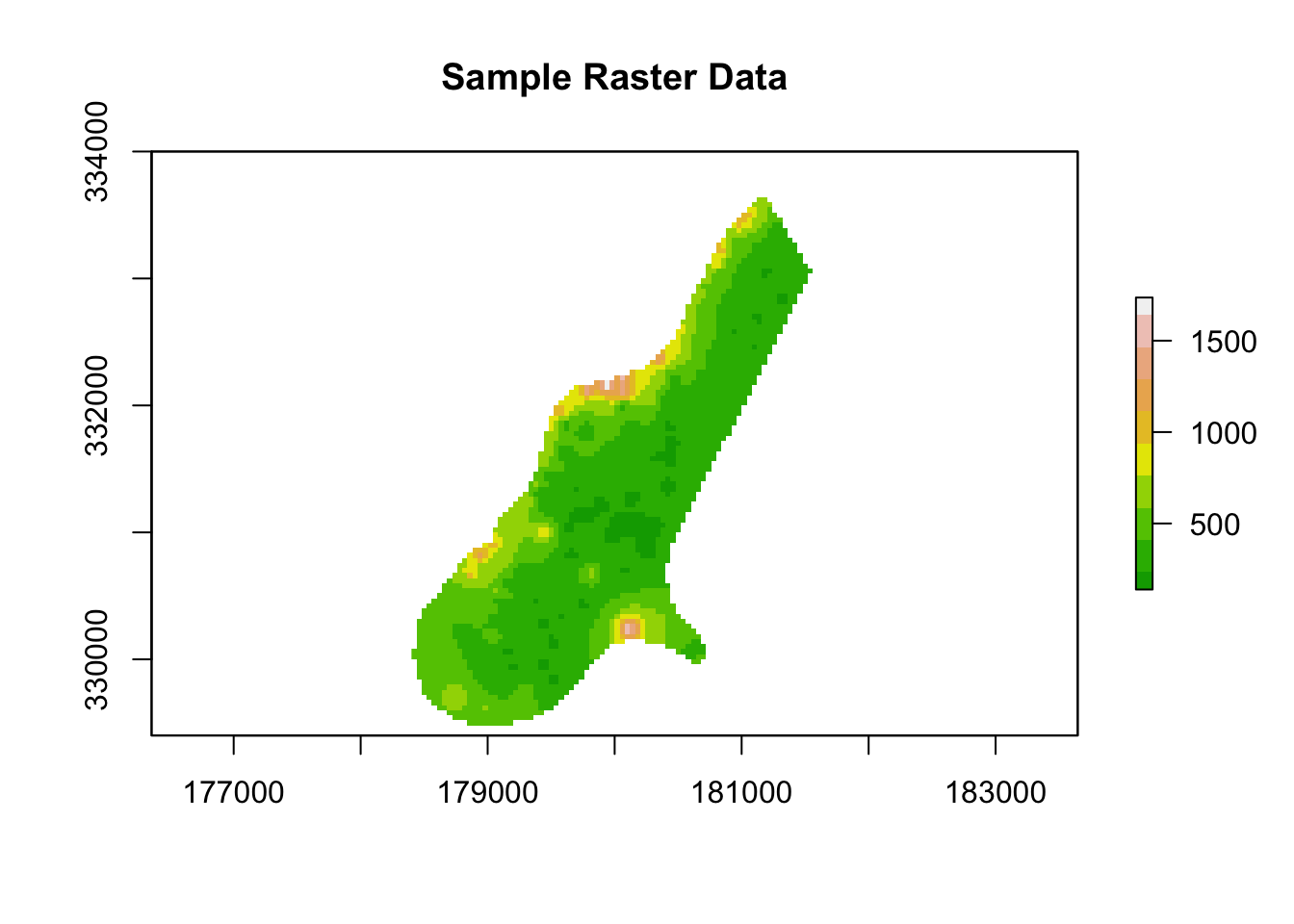

Now, let’s load a sample raster dataset, also provided by the raster package.

# Load a sample raster file (comes with the 'raster' package)

raster_path <- system.file("external/test.grd", package = "raster")

raster_data <- raster(raster_path)

# Print raster information

print(raster_data)

#> class : RasterLayer

#> dimensions : 115, 80, 9200 (nrow, ncol, ncell)

#> resolution : 40, 40 (x, y)

#> extent : 178400, 181600, 329400, 334000 (xmin, xmax, ymin, ymax)

#> crs : +proj=sterea +lat_0=52.1561605555556 +lon_0=5.38763888888889 +k=0.9999079 +x_0=155000 +y_0=463000 +datum=WGS84 +units=m +no_defs

#> source : test.grd

#> names : test

#> values : 138.7071, 1736.058 (min, max)

# Plot the raster

plot(raster_data, main = "Sample Raster Data", col = terrain.colors(10))

4.3.0.2 5.2. Writing Spatial Data to Disk

Once you’ve processed your spatial data, you’ll often want to save it to disk for sharing or future use. Let’s see how to save both shapefiles and rasters.

4.3.0.2.1 Saving a Shapefile

# Define output file path

output_shapefile <- "output_shapefile.shp"

# Save the shapefile to disk

shapefile(shape_data, filename = output_shapefile, overwrite = TRUE)

# Confirm the file was created

list.files(pattern = "output_shapefile*")

#> [1] "output_shapefile.cpg" "output_shapefile.dbf"

#> [3] "output_shapefile.prj" "output_shapefile.shp"

#> [5] "output_shapefile.shx"- The

shapefile()function writes aSpatial*object to disk in shapefile format. - Always set

overwrite = TRUEif you want to overwrite existing files.

4.3.0.2.2 Saving a Raster

Let’s save the raster we read earlier to a new file in GeoTIFF format.

# Define output file path

output_raster <- "output_raster.tif"

# Save the raster to disk

writeRaster(raster_data, filename = output_raster, format = "GTiff", overwrite = TRUE)

# Confirm the file was created

list.files(pattern = "output_raster*")

#> [1] "output_raster.tif"- The

writeRaster()function writes raster data to various formats, including GeoTIFF, NetCDF, and ASCII Grid. - Set

format = "GTiff"to specify the file format as GeoTIFF.

4.3.1 Key Takeaways

- Use

shapefile()to read and write shapefiles. - Use

raster()andwriteRaster()for reading and saving raster data. - The

system.file()function is useful for accessing sample datasets bundled with R packages. - Always check the CRS, resolution, and extent of your data to ensure proper alignment when saving files.

4.4 ### 6. Practical Applications in SDM

Species Distribution Modeling (SDM) involves predicting the geographic distribution of species based on environmental data (e.g., climate variables) and species occurrence data (e.g., observed locations of a species). In this section, we’ll demonstrate how to:

-

Download environmental data using the

getData()function from thedismopackage.

-

Retrieve species occurrence data from GBIF using the

gbif()function.

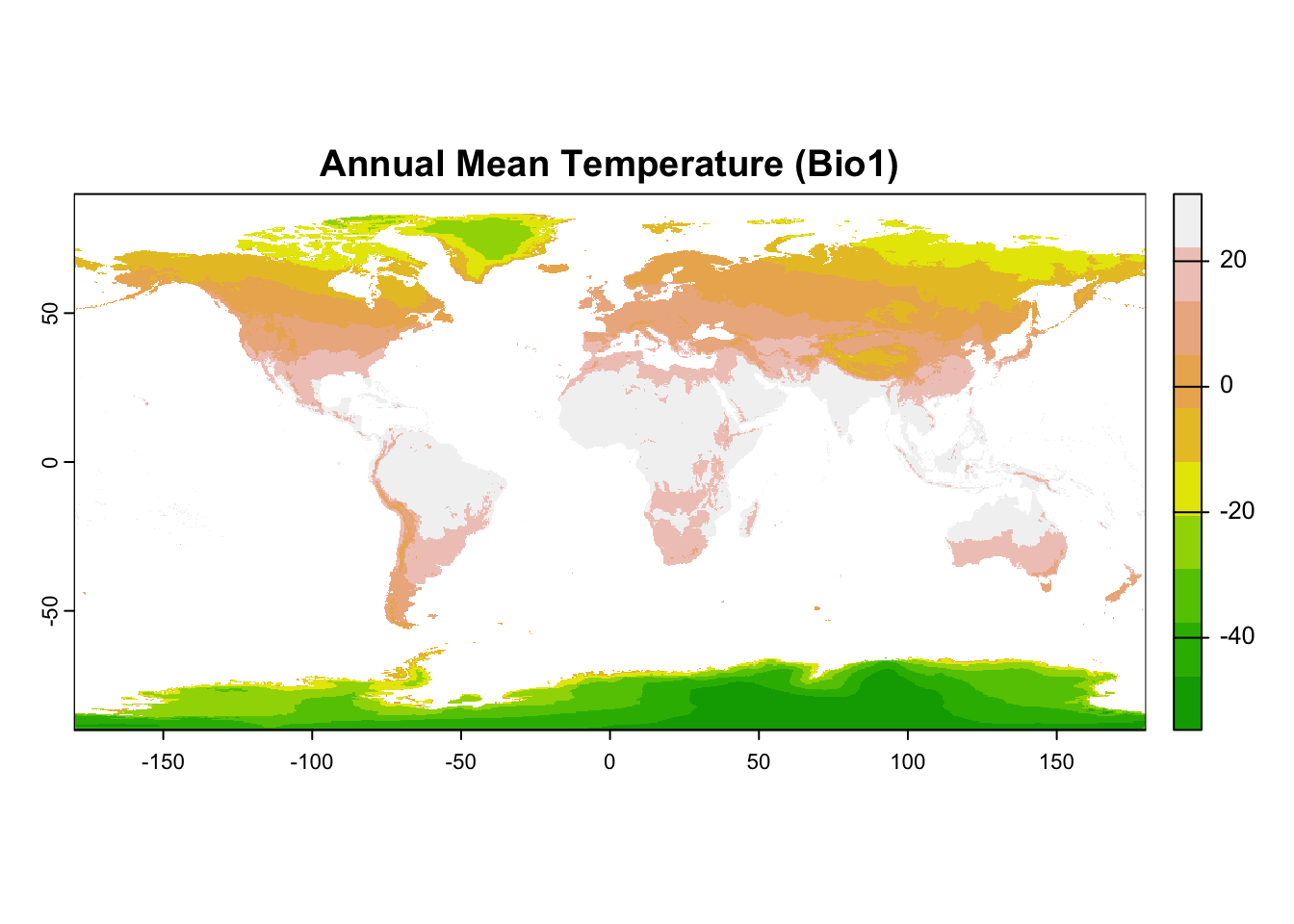

4.4.0.1 6.1. Downloading Environmental Data

Bioclimatic variables are commonly used in SDM. These variables represent different climate characteristics, such as annual mean temperature, temperature seasonality, and annual precipitation.

# Load necessary library

library(geodata)

# Specify a directory to save the data

data_path <- tempdir() # Temporary directory for demonstration purposes

# Download bioclimatic variables at 10-minute resolution

bioclim_data <- worldclim_global(var = "bio", res = 10, path = data_path)

# Check the structure of the raster stack

print(bioclim_data)

#> class : SpatRaster

#> dimensions : 1080, 2160, 19 (nrow, ncol, nlyr)

#> resolution : 0.1666667, 0.1666667 (x, y)

#> extent : -180, 180, -90, 90 (xmin, xmax, ymin, ymax)

#> coord. ref. : lon/lat WGS 84 (EPSG:4326)

#> sources : wc2.1_10m_bio_1.tif

#> wc2.1_10m_bio_2.tif

#> wc2.1_10m_bio_3.tif

#> ... and 16 more sources

#> names : wc2.1~bio_1, wc2.1~bio_2, wc2.1~bio_3, wc2.1~bio_4, wc2.1~bio_5, wc2.1~bio_6, ...

#> min values : -54.72435, 1.00000, 9.131122, 0.000, -29.68600, -72.50025, ...

#> max values : 30.98764, 21.14754, 100.000000, 2363.846, 48.08275, 26.30000, ...

# Plot the first bioclimatic variable: Annual Mean Temperature (Bio1)

plot(bioclim_data[[1]], main = "Annual Mean Temperature (Bio1)", col = terrain.colors(10))

- The function

getData()retrieves bioclimatic variables from the WorldClim dataset.

-

var = "bio"specifies that we want bioclimatic data, andres = 10sets the grid resolution to 10 minutes. - The result,

bioclim_data, is a RasterStack containing multiple environmental layers.

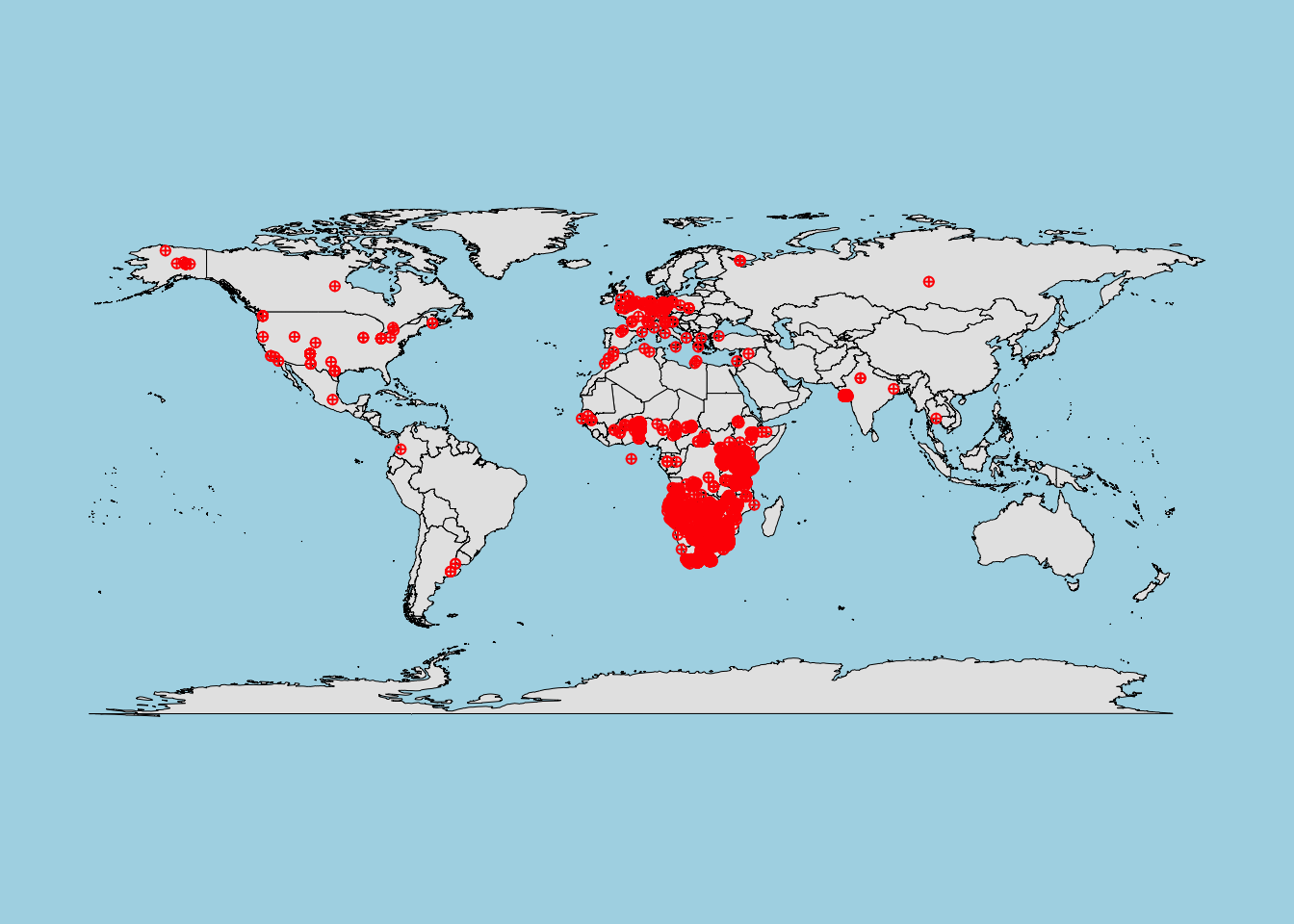

4.4.0.2 6.2. Retrieving Species Occurrence Data

The Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF) provides open-access data on species occurrences worldwide. Let’s retrieve occurrence data for the African lion (Panthera leo).

# Load necessary library

library(dismo)

# Define a file path to save the data

file_path <- "lion_gbif_data.rds"

# Check if the data already exists locally

if (file.exists(file_path)) {

# Load the data from the local file

lion_data <- readRDS(file_path)

message("Data loaded from local file.")

} else {

# Retrieve the data from GBIF and save it locally

lion_data <- gbif(genus = "Panthera", species = "leo")

saveRDS(lion_data, file_path)

message("Data downloaded and saved locally.")

}

#> Data loaded from local file.

# Subset the first 300 records for demonstration

lion_data_subset <- lion_data

# to limit the point to view, for example, 3000 points:

# lion_data_subset <- lion_data[1:3000, ]

# Plot the occurrence data on a world map

library(maps)

map("world", col = "gray90", fill = TRUE, bg = "lightblue", lwd = 0.5)

points(lion_data_subset$lon, lion_data_subset$lat, col = "red", pch = 10, cex = 0.7)

-

Data quality check:

Always inspect GBIF data for missing values and incorrect coordinates before using it in models.

In particular, check forNAvalues in the longitude (lon) and latitude (lat) columns.

4.4.1 7. Summary and Key Takeaways

In this tutorial, we covered several essential steps for working with spatial data in R, particularly focusing on Species Distribution Modeling (SDM).

4.4.1.1 Summary Table

| Concept | Key Functions | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Vector Data |

st_as_sf(), st_transform()

|

Creating, transforming, and plotting vector data. |

| Raster Data |

raster(), stack(), writeRaster()

|

Creating and manipulating raster layers. |

| CRS Handling |

st_crs(), project()

|

Checking and transforming Coordinate Reference Systems (CRS). |

| Environmental Data | getData() |

Downloading global bioclimatic variables for SDM. |

| Species Occurrence Data | gbif() |

Retrieving species occurrence data from GBIF. |

4.4.2 Key Takeaways

- Always ensure that your spatial datasets share the same CRS before performing any analysis.

- Use reliable sources for environmental data, such as WorldClim, and carefully inspect species occurrence data from GBIF.

- Properly handle and visualize both vector and raster data in R using functions from packages like

sf,raster, anddismo.

4.5 Task

Try and do the following tasks to test your knowledge:

4.5.1 Next Steps

In the next part, we will dive deeper into:

-

Advanced spatial analysis techniques:

- Buffering, spatial joins, and overlay operations.

-

Building SDMs:

- Using machine learning methods (e.g., MaxEnt, Random Forest) to predict species distributions.

-

Predictive modeling:

- Projecting species distributions under future climate scenarios using environmental datasets.